First off, what exactly is a pyramid scheme?

A pyramid scheme, also known as a “multi-level marketing” scheme or an MLM, is a popular form of direct selling that involves using one’s social connections to grow a business network. A 1996 academic journal defined direct selling as “face-to-face selling away from a fixed retail location”, usually involving meeting people in social, non-business situations in order to promote the business.

So, isn’t this just affiliate marketing, then?

Well, yes and no. Direct selling and affiliate marketing have very similar contexts and are often used interchangeably, but not all direct selling can be described as multilevel marketing. Within the direct selling industry, there is a particular type of compensation scheme used by most of the popular MLM companies, where sellers are compensated not just for the sales they personally generate. They are also rewarded for the sales generated by the people they recruit, who often form what is described as a “downline”. Because participants can be compensated through multiple levels of recruits (meaning they earn rewards on those they recruit, and also those in their recruits’ downlines, etc.), this is often called multilevel marketing. Since recruits are often encouraged to leverage personal networks in order to build a downline, MLMs are also sometimes referred to as “network marketing.”

MLMs constitute a massive, global industry, with recent estimates of sales as high as ninety billion, while estimates of the reach of such businesses and organisations indicate that as many as half of all respondents had purchased at least one item from an MLM prior to reporting.

So, what exactly is the issue with MLM?

The main issues with MLMs appear to be ethical and structural, meaning that there are often moral issues resulting from the unique business structure. MLMs will often ask people to make a significant initial investment (often framed as some form of “license”) to recruit others who, in turn, pay the same entry fees and recruit others into the scheme. So, in essence, the initial investment was for the opportunity to receive compensation off someone else’s investment, meaning the opportunity to recruit is the actual product.

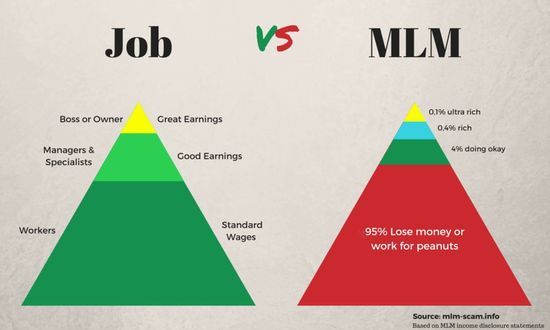

Firstly, such a scheme is unethical because it promises profits and success not based on legitimate marketing and sales of a verifiable product, but on one’s ability to persuade others to invest their own money in a business. Because such a business is not engaged in normal profit and loss, over time the initial capital (generated from investments) runs out and the business collapses. For this reason, those who found MLMs or join early often make a great deal of money, while those recruited later make little or even lose money because capital has been drained to compensate early adopters and there simply are not enough remaining funds or people left available to the network. The second reason such a business is unethical is that it is not in the public interest to have businesses that are focused on recruitment, rather than delivering a product or services to consumers; keeping a business focused on achieving an aim of “public good” helps the business to have sensible and achievable goals, allows them to be accountable to consumers and stakeholders, and ensures that the business will maintain public interest and benefit (which is important for profitability). A business that is focused on “recruitment” and relationships will struggle with understanding and maintaining normal benchmarks and guardrails for a business (such as profit margins, consumer protection, customer service, etc.) and may veer off into unsavory or exploitative practices without proper controls. These reasons are primarily why so many MLMs are often engulfed by accusations of fraud and dispossession and why the term has taken on such a negative connotation in some circles.

Fraudulent MLMs also have a reputation for targeting some of the more vulnerable members of society (such as immigrants, the disabled, stay-at-home or single mothers, college students, and people in developing countries) for scams. Such individuals often have greater and more pronounced financial difficulties, as well as fewer opportunities for advancement and success, so such schemes often appear to be god-sent and are often not questioned as critically; for this reason, it is also particularly damaging and heartbreaking for such individuals when they lose money to MLM scams.

So, are ALL MLMs bad?

Well, not necessarily, but I would say that the vast majority will likely be unprofitable for most people who engage in them. As mentioned earlier, the main issues with MLMs arise as a result of 1) lack of standardised, marketable products, and 2) misguided or exploitative profit generation, so paying attention to those factors can always help you understand if a new business being pitched to you is a predatory MLM or not. This is however not always the easiest thing to do, especially when such businesses are promising fantastic profit margins, so here are five questions to ask yourself before putting your hard-earned money in a new business franchise:

How Is the Money Being Made?

If the money is being made solely or primarily from recruitment, walk away. A healthy business should have reasonably popular goods or services to sell in order for franchisees to make profit. If you don’t know or properly understand what the business sells, no matter how “good the money is” or how “easy it is to do”, walk away. If you are uncomfortable with how the money is made, either because you question the business model or are uncomfortable approaching your social network to sell things to them, walk away. An MLM, of any kind, is not likely to be a good experience for you.

Are There any Products, and Are They Legitimate?

Again: do you know what you’re selling? Can you vouch for the existence and/or quality of what you’re selling? Have you used it yourself? Can you actually recommend this product or service to others, without the incentive of a commission? If you struggle on any of these questions, you need to take a step and really ask yourself if this business is right for you.

How Much Does It Cost to Be Involved?

Most legitimate businesses, even franchises, will only ask you to pay for setup costs and the price of your inventory. Businesses that require pricey registration or licensing fees, which are often not refundable or recoupable after payment, are not showing signs of strength or resilience, and this may be a red flag for a troubled or faulty business model. So, even if the promises of profit are astonishingly high, any MLM business with exorbitant startup costs should be looked at with scepticism.

How Much Work Is Required?

This right here is the trick question. Most people expect that it is the overly complex, or very difficult-sounding job that is the suspicious one, but any MLM that promises you can earn income with little or no difficulty or stress should immediately raise your red flags. Money is not easy to come by, even for those who come by it fraudulently, so whenever someone tells you there’s a “secret” money-making formula to their MLM, take your own money and run!

How Long Has The Company Been Around?

Most MLMs, for reasons detailed above, are notoriously shortlived. While this bodes poorly for those who invested in that particular business, it offers a ray of hope to those of us looking to avoid a similar fate. Longevity is often a good way of gauging how legitimate an MLM is, as a more honest or better run scheme will not struggle with income generation and will therefore stay afloat longer. A business that has been around just a year or two but is “rapidly growing” shouldn’t even pique your interest. A business that was popular two years ago but has largely cooled in interest is a no-go area. Any MLM that has kept the doors open for five years or more can likely be trusted, but you are still advised to go in with your eyes open and a firm eye on your wallet.

To Conclude: The Crypto Of It All.

Back when I originally wrote this article, I wasn’t really planning on talking specifically about crypto, even though it was actually an offer to invest in crypto that sparked my interest in writing about this. A person that I had only recently gotten to know contacted me about an “amazing business opportunity” that I was then too nice to immediately reject. I agreed to meet and discuss it, and during the conversation this person, a young man, divulged that the “business” was a new cryptocurrency that had apparently been making the rounds on social media and generating a fair bit of buzz. I was extremely skeptical, but I decided to hear him out since I had gone to the trouble of making the meeting. He recounted how he had been going through a tough time financially, and how this had affected his family and their living situation, but now had hope because of this cryptocurrency. The setup involved downloading some app with a number of gamified activities to give the appearance of user agency, but the gist of it was that you needed to invest a certain amount (there were the usual investment “tiers” you find in most MLMs), and recruit other investors “beneath you” to boost your own investment’s value.

So, like, an actual pyramid scheme.

I wanted to warn this person about the severe doubts I had about this “business”, but he had the bright-eyed look of a new convert (we had, incidentally, met through church) and didn’t seem open to having holes poked his hopes of prosperity. So I decided to write this instead, in the hopes that other people in similar situations would read it and be better protected.

So, to address the issue directly: is crypto a pyramid scheme/MLM?

Short answer: Yes.

Slightly longer answer: It’s complicated, but yes.

The profit model championed through cryptocurrency is almost identical to the one used by most MLMs. Most of them aren’t as explicitly identical as the one in my anecdote, but the core principle remains the same: your investment generates profits, not through the creation of useful goods or provision of in-demand services, but through the real or expected injection of new investment, either from you or from others. Without a meaningful public interest or good outside of profit growth, cryptocurrency remains in a strange limbo: it doesn’t do anything but exist, and so there is no motive for anyone other than a potential investor to interact with it, and its growth potential is strangled. Where a product like, say, a brand of peanut butter, or a service like a rideshare app, can experience value growth through sales or partnerships as well as investment, crypto can only grow as a result of actual investment or the expectation that investment will occur. If that investment fails to occur, or worse, if enough people pull their money out, the value will crater, creating a feeding frenzy of people rushing to sell, which will annihilate the value of those crypto assets.

So, doesn’t that just make crypto like an actual currency?

In some ways, yes. It’s literally in the name cryptocurrency. But crypto differs from “normal” currency in some crucial ways that make trading it a much more risky investment than normal forex trading. Ordinary currencies are often backed and secured by the central banks of the countries where they are produced, and their value is pegged to the economic performance of those countries. This gives these currencies a form of stability that allows people who trade in them to rely on them as a meaningful, reliable source of value generation. Regardless of one’s moral stance on foreign exchange trading, there is at least a real (if parasitic) model of value generation with long-term stability. As long as the country in question continues to trade in goods and services, both internally and externally, its currency can be expected to maintain or grow in value, and as long as the country’s central bank continues to exist, there is a process by which that currency can be exchanged to produce meaningful profits for a forex trader.

Crypto, on the other hand, is by nature decentralized, which means there is no central bank securing it, so its value can only be tangentially and questionably linked to that of more stable assets. This also means that there is no institution or entity to turn to if one’s crypto is lost, stolen or suddenly crashes in value. The owner bears all the risk alone.

The lack of centralization also leads to another problem: a lack of regulation. No regulation means that there are no “official” channels through which one can securely trade crypto, leaving one at the mercy of privately-run exchanges with no government oversight. This leaves crypto holders as vulnerable as someone who chooses to bank with a loan shark, but also means that one is never sure about the moral character of those with whom one is trading crypto. Crypto’s primary value as a currency is in its anonymity, which is perhaps why it has become a favorite of unsavory characters looking to conceal or launder ill-gotten wealth.

So, to conclude, if the ethical questions aren’t off-putting, and the glaring risk of total loss of investment with no recourse for recovery is also not a dealbreaker, then one might consider putting money in crypto. But, and this is just my humble perspective, something that seems to blend the worst parts of forex trading and MLMs is not a “business” I would rush headlong into. Watch out.